Deriving secrets from signatures

To solve the painful seed fatigue problem for users of existing private protocols we need a solution that works today. The key is to use cryptographic primitives that wallets already support to build a robust and secure derivation protocol.

Of course, this is not the first attempt to solve this problem. It is worth looking at previous efforts to understand the trade offs and why a new approach is necessary. Several proposals have attempted to address this problem, but each has different trade offs.

BIP-85 ("Deterministic Entropy from BIP-32 Master Seeds") exports per application entropy directly from the wallet's master seed. However, it is only available on a subset of hardware, leaks raw entropy without human readable context, and offers no domain separation guarantees. These issues motivate a signature based approach that is compatible with modern wallets without exposing the mnemonic.

EIP-1775 ("App Keys") targets web dApps by deriving a key via keccak256(parentPrivKey‖origin). This approach requires special firmware support for hashing the parent key, offers no structured EIP-712 consent prompt, and allows any script within the web origin to silently extract the derived key.

The naive derivation problem

A simple approach, such as deriving a secret from signing a fixed hash like sign(keccak256('my_app_secret')) suffers from several vulnerabilities:

- No informed consent: The signing prompt is opaque. It fails to communicate the operation's purpose, asking the user to "blind sign" a hexadecimal string without context.

- Poor domain separation: A signature produced for one application could potentially be replayed and used in a different application or context, as the signed message lacks a unique application identifier.

- Phishing risks: Because the message is fixed and public, a phishing website can ask a user to produce the exact same signature. The phisher can then steal this signature and use it on the legitimate application to reconstruct the user's secret and compromise their account.

A robust derivation protocol must therefore be designed from the ground up to prevent these failures. We design a four step mechanism to provide strong domain separation, phishing resistance, and informed consent by creating a challenge response that is not only unique to the user but also undiscoverable by a malicious actor.

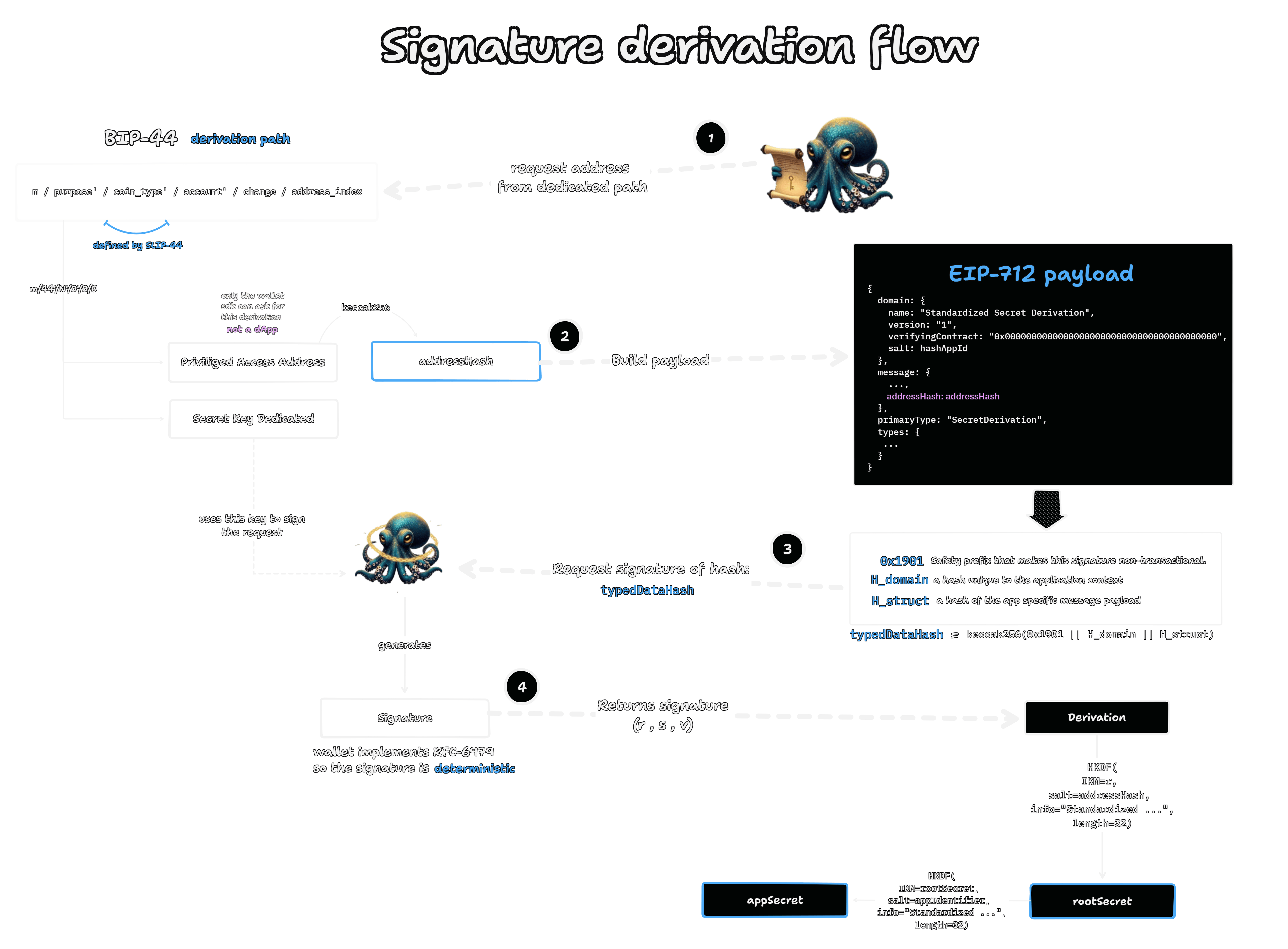

This chapter will walk through the mechanics of this signature based protocol, which is designed to be fully implemented in software. As the diagram visualizes, we can explore it as a four step process flowing from the user's master seed to a final, application ready secret.

(Step 1)We derive a special purpose, undiscoverable key inside the wallet.(Step 2)We use its address to construct an unforgeable EIP-712 challenge.(Step 3)We request a deterministic signature over that challenge using the key itself.(Step 4)We extract entropy from the signature to derive the final application secret.

Let's unpack how each of these steps works and why this specific construction is secure.

The mechanism, a four step protocol

Before diving in, it is helpful to define a few key terms. The user's Master Seed is the primary secret (typically a BIP-39 mnemonic) that must never leave the wallet. From this, we use a Dedicated Path (a unique BIP-44 path) to derive a private key whose public address we will call the Privileged-Access Address. The core of the protocol involves transforming cryptographic values from this address and a signature into a final appSecret for the application.

Step 1, deriving the undiscoverable address

The protocol's phishing defense is built on a security model of differing levels of privilege. Think of the wallet's software like a browser extension and a dApp website as operating in two separate security zones. By design, the wallet has higher privileges than the websites it interacts with.

This is a security decision of web3 browsers, the window.ethereum Provider API (EIP-1193) that a dApp uses is intentionally minimalistic. It acts as a sandboxed, high level interface that prevents a website from performing dangerous low level actions. A dApp can ask for the user's active account (eth_requestAccounts) but it cannot, for example, ask the wallet to reveal an address from an arbitrary derivation path like m/44'/N'/0'/0/0.

This security model relies on the integrity of the wallet software itself. If a malicious actor can convince a user to install a compromised wallet clone, this sandboxing is defeated, and the user's master seed is at risk. This is a trust assumption in all wallet interactions.

The wallet's own SDK, however, operating as a privileged actor, is not bound by this sandbox. It can use lower level libraries to communicate directly with the wallet's keystore. As seen in the diagram (Step 1), only the Wallet SDK can request the address from this dedicated path, making the resulting Privileged-Access Address effectively undiscoverable by a standard dApp.

// Step 1: Derive dedicated address

const dedicatedPath = `m/44'/${coinType}'/0'/0/0`;

const signerAddress = await walletClient.request({

method: 'wallet_getAddressFromPath',

params: [dedicatedPath]

});

if (!isAddress(signerAddress)) {

throw new Error('Invalid address derived from dedicated path');

}

Step 2, building the EIP-712 challenge

The next step is to prove control over the master seed by signing a message. We construct an unforgeable challenge by including an addressHash within the EIP-712 payload. This addressHash is the core of the protocol's phishing defense, it's the keccak256 hash of the Privileged-Access Address from Step 1. Because a phishing site cannot generate this value, any signing request it crafts will be invalid, making the challenge unique to the user's master seed and secure against forgery.

EIP-712 is the ideal tool for this because it ensures signatures can be deterministically replicated (crucial for recovery), provides strong cross context replay resistance (prevents signatures from being used elsewhere) and enables informed user consent through a human readable format.

const addressHash = keccak256(toBytes(signerAddress));

const eip712Payload = {

domain: {

name: "Standardized Secret Derivation",

version: "1",

verifyingContract: "0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000",

salt: keccak256(toBytes(appIdentifier))

},

message: {

purpose: "This signature is used to deterministically derive application-specific secrets from your master seed. It is not a transaction and will not cost any gas.",

addressHash: addressHash

},

primaryType: "SecretDerivation",

types: {

EIP712Domain: [

{ name: "name", type: "string" },

{ name: "version", type: "string" },

{ name: "verifyingContract", type: "address" },

{ name: "salt", type: "bytes32" }

],

SecretDerivation: [

{ name: "purpose", type: "string" },

{ name: "addressHash", type: "bytes32" }

]

}

} as const;

The security of EIP-712 comes from its use of a domain separator. Think of a signature as a key and the message context as a lock. The domain separator ensures that every application has a different, unique lock. A signature generated for Application A (the key) simply will not fit in the lock for Application B. This is achieved by hashing several components together into the final typedDataHash that gets signed.

Let's look at what each part does:

0x1901: This is a simple but important safety prefix. It essentially marks the data as "not a transaction" which prevents a malicious dApp from taking a signature for something mean and tricking a contract into interpreting it as an order to move funds. It's a legacy protection against a certain class of replay attacks.H_domain: This is the "lock" we mentioned before. It is a hash of the application's unique context, including itsname("Standardized Secret Derivation") andversion(like "1"). This ensures a signature for our protocol cannot be maliciously replayed on another dApp's platform, because that platform would have a different domain name, and thus a different lock.H_struct: IfH_domainis the lock,H_structis the unique fingerprint of the document being signed. Any change to the message, even a single character, would result in a completely differentH_struct, making the signature invalid. This guarantees the integrity of what the user is actually signing.

It's worth noting there's a design trade off here. Our protocol uses a single, protocol wide H_domain for all apps that use it. For example, a user performs one signature for the "Standardized Secret Derivation" domain. From the resulting signature, we can then derive secrets for both Privacy Pools and Railgun. This is great for UX, one signature unlocks privacy everywhere. An alternative design would be to create a unique domain for every app. This would require the user to sign a new message for every time, adding friction but creating even stronger isolation at the signature level. We opt for the former, prioritizing a seamless UX.

Step 3, requesting the signature

Now, we request the signature, the most secure way to do this is with what we can call a self referential cryptographic attestation. This is a term for a simple but powerful idea, we ask the wallet to sign the EIP-712 message not with the user's primary 0x account, but with the private key corresponding to the Privileged-Access Address itself.

This creates a cryptographically closed loop. Let M be our EIP-712 message. M contains a hash derived from the Privileged-Access Address. The signature S is then Sign(sk_dedicated, M). The signature S serves as an undeniable proof. This signature serves as an internal proof within the wallet SDK context because it knows the Privileged-Access Address requested in Step 1, it could mathematically verify that the key used to create S corresponds to that same address. This confirms that the wallet correctly used the specific private key tied to the challenge. However, this check is an internal consistency guarantee, not a proof for any outside observer.

This chain of proof is enabled by deterministic signatures. When the SDK calls eth_signTypedData_v4, wallets implementing RFC 6979 will generate the ECDSA signature in a predictable way. This is the absolute cornerstone of the protocol's recoverability. If a user moves to a new device, they must be able to regenerate the exact same appSecret using only their master seed. This is only possible if every step, including generating the signature's r value, is deterministic.

// Step 3: Request signature

const signature = await walletClient.signTypedData({

account: signerAddress,

domain: eip712Payload.domain,

types: eip712Payload.types,

primaryType: eip712Payload.primaryType,

message: eip712Payload.message

});

const { r, s, v } = hexToSignature(signature);

// Securely destroy s and v components (only r is used for derivation)

const rValue = r;

s = null; // Destroy s component

v = null; // Destroy v component

Step 4, deriving the secret

The final step is a two stage key derivation using HKDF-SHA256. This process must happen in a privileged context, which in practice means it is executed by the wallet software or its most trusted SDK components. The user's guarantee of this is their trust in the wallet software itself, the same trust they place in it to sign transactions securely.

Stage 1, Root Secret

First, we derive an ephemeral rootSecret. The purpose of this intermediate step is cryptographic hygiene. It allows us to distill a clean, high entropy secret from our inputs before mixing in application specific data. We create it by combining the two deterministic values we've generated: the signature's r value and the Privileged-Access Address.

This rootSecret is now a pure representation of the user's identity for this protocol, but it is not yet tied to any app. It must be treated as a highly sensitive value and never be exposed outside its secure context.

Stage 2, the appSecret

Next, as shown in the final step of the diagram, we derive the final appSecret from the rootSecret. This time, we use a unique, public application identifier (like a reverse domain name as PrivacyPools) as the salt.

This two step KDF ensures that each application receives a unique, cryptographically isolated secret. This final appSecret is the only value that is returned to the requesting application, which can then use it as the root for its own internal key hierarchies.

// Step 4: Derive root secret

const rBytes = hexToBytes(rValue);

const saltBytes = hexToBytes(signerAddress);

const rootInfoBytes = new TextEncoder().encode("Standardized-...-v1-Root");

const rootSecret = hkdf(sha256, rBytes, saltBytes, rootInfoBytes, 32);

// Step 5: Derive application secret

const appSaltBytes = new TextEncoder().encode(appIdentifier);

const appInfoBytes = new TextEncoder().encode("Standardized-...-v1-App");

const appSecret = hkdf(sha256, rootSecret, appSaltBytes, appInfoBytes, 32);

// Securely wipe root secret

rootSecret.fill(0);

return bytesToHex(appSecret);

The rootSecret is not limited to generating only one secret per app. A dApp can call the HKDF Expand step multiple times with the same rootSecret but different info strings to efficiently derive any number of purpose specific keys.

For example, an application like Privacy Pools could generate a single rootSecret and then immediately derive multiple secrets needed for a user action:

nullifierKey = HKDF-Expand(IKM=rootSecret, info="pp-nullifier-v2", ...)

revocationKey = HKDF-Expand(IKM=rootSecret, info="pp-revocation-v2", ...)

noteSecret = HKDF-Expand(IKM=rootSecret, info="pp-note-v2", ...)

Conclusion

This signature based derivation protocol is a practical, secure, and immediately deployable solution to the seed fatigue problem that plagues the privacy ecosystem. By cleverly combining existing, well supported standards like BIP-44, EIP-712, and RFC 6979, we can construct a phishing resistant system that works with the wallets millions of people already use.