The proof

We have established that the protocol's privacy comes from using private notes (as explained in Anatomy of a note). But this creates a fundamental paradox: to withdraw your funds, you must prove to a public smart contract that you own a specific note, yet revealing any information about that note would destroy your privacy.

The answer is Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs). More specifically, a type of ZKP called a zk-SNARK (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge). This is the cryptographic engine that makes the entire system possible.

A ZK-SNARK lets an untrusted Prover (your wallet) convince a Verifier (a smart contract) that it knows a secret (witness) that makes a statement true, all without revealing the secret itself. The goal is to create a proof that is:

- Succinct: The proof itself is very small, making it cheap to store and process on the blockchain.

- Fast to Verify: It's much faster for the contract to check the proof than to re-do the original-computation.

- Zero-Knowledge: The verifier learns nothing about the secret witness other than the fact that the statement is true.

This document will walk through a practical, end-to-end example of how a ZK-SNARK is used to power a private withdrawal.

An end to end withdrawal example

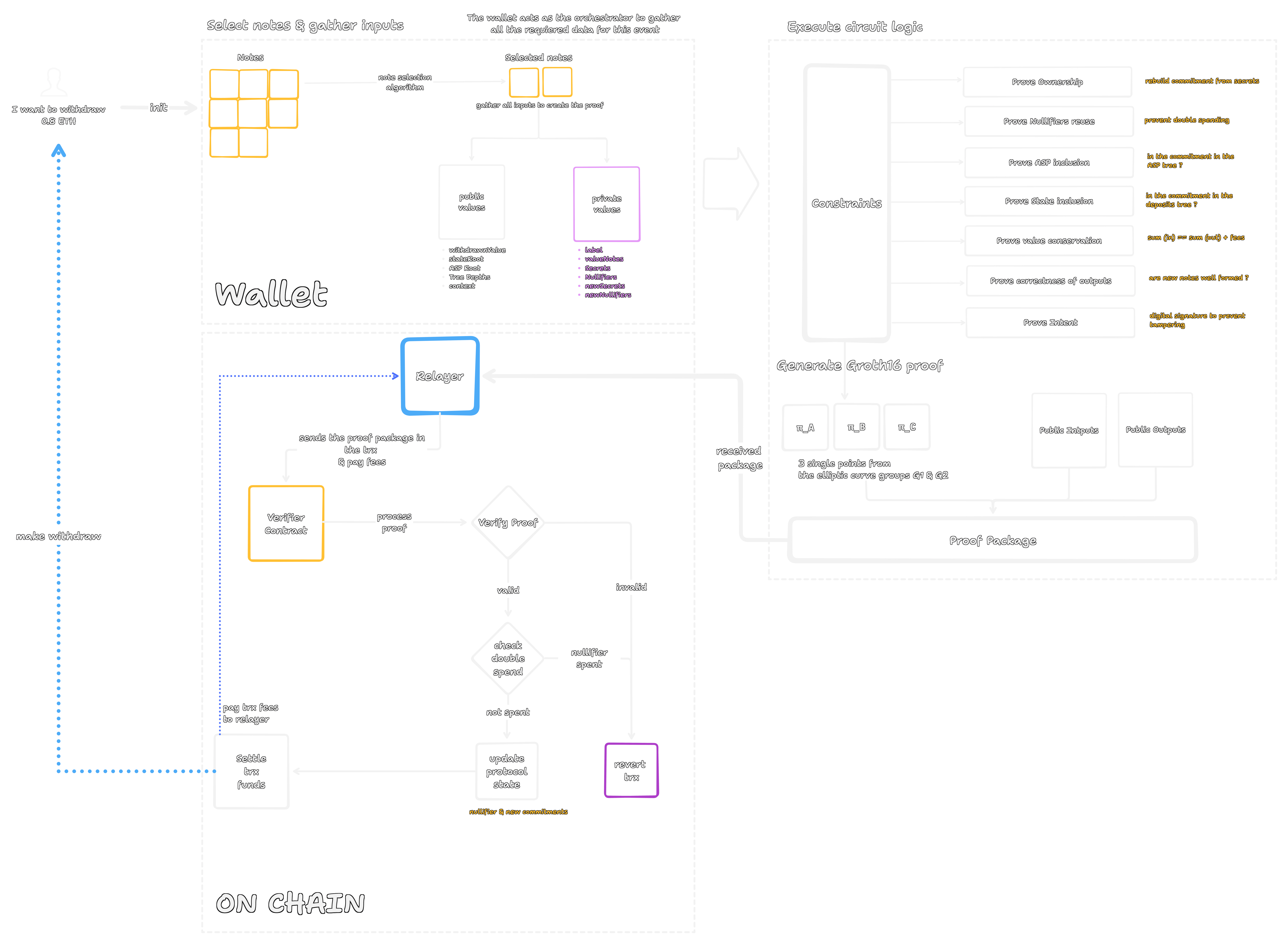

This example explains the whole process for a private withdrawal transaction and how the system uses a zk-SNARK to prove the validity of the operation without revealing the user's private data.

The Statement: "I want to withdraw 0.8 ETH. I am proving ownership of two unspent 0.5 ETH notes. The proof includes the corresponding nullifiers to prevent double spending and a new commitment for the resulting 0.2 ETH change note."

Off Chain proof generation (client side)

The process is initiated when the user requests a withdrawal of 0.8 ETH. All of the following computations occur on the user's local machine. First, the wallet's note selection algorithm determines the optimal set of input notes from the user's holdings. For this example, it selects two 0.5 ETH notes. It then gathers and partitions the required data for the proof's witness:

- Private inputs: This secret data is known only to the user. It includes the

secretandnullifierfor each of the two input notes, along with their respective Merkle proofs (siblings,indices) against the known state. It also contains the secret data for the new 0.2 ETH change note. - Public inputs: This data will be submitted to the chain for verification. It includes the

withdrawnValue(0.8), the targetstateRootandASPRoot, and acontextvalue to prevent replay attacks.

These inputs are processed by the Withdrawal.circom circuit, which enforces a set of constraints. The proof is valid only if all constraints are met for the entire batch of input notes, some constraints for the circuit are:

- Prove ownership: Verifies that the private inputs correctly reconstruct the commitments for both input notes.

- Prove ASP/State inclusion: Verifies that both input notes are present in the Merkle trees corresponding to the public

ASPRootandstateRoot. - Prove value conservation: Verifies that the sum of input note values equals the sum of outputs (

(0.5 + 0.5) = 0.8 + 0.2). - Prove nullifier non reuse: Enforces that the nullifiers of the input notes are correctly computed and have not been previously revealed.

If all constraints are satisfied, the Groth16 protocol is used to generate a succinct proof consisting of three elliptic curve points: $ \\pi_A, \\pi_B, \\pi_C $.

The output of the client side process is a Proof Package and it contains the Groth16 proof and all public inputs and outputs (e.g., withdrawnValue, newCommitmentHash, existingNullifierHashes). Finally the package is then sent to a Relayer for submission to the blockchain.

On chain verification and state update

The Relayer submits the Proof Package in a transaction to the Verifier Contract. The contract then executes two primary verification steps.

- Proof Verification: The contract performs a pairing check. It uses a preconfigured

Verification Key(unique to theWithdrawalcircuit) to mathematically verify theGroth16proof against the public inputs. If the check fails, the proof is invalid, and the transaction reverts. - Double spend check: If the proof is valid, the contract checks for double spending. It takes the existing nullifier hashes from the public inputs and checks for their existence in an onchain mapping of already spent nullifiers. If either nullifier is found in the mapping, the transaction reverts.

If both verification steps succeed, the contract proceeds to settle the transaction and update the protocol state:

- Settle funds: Transfers the

withdrawnValue(0.8 ETH) to the specified recipient address. - Update state: Atomically adds the nullifiers to the onchain set of spent nullifiers and inserts the

newCommitmentHash(for the 0.2 ETH change note) into the deposits Merkle tree.

The transaction is now complete.

Conclusion and next steps

The ZK Proof is the protocol that enables private transactions. It's a small packet of data, generated securely on your own device, that convinces a public contract that you are authorized to move funds without revealing any of your private information.

However, a perfect proof doesn't solve the whole problem. Even if the proof itself is anonymous, the act of submitting it to the blockchain is not. If you pay the gas fee for the transaction from your public 0x address, you create a direct, public link to your private action. We've hidden the what, but we still need to hide the who is performing the action. This is the "last mile" problem of privacy and it's solved by the Relayer.