Mapping the derivation attack surface

Our last discussion ended with the creation of a powerful 512bit master seed a single root of trust generated from our 12 mnemonic words. But the story doesn't end there, we don't use this master seed directly for every transaction. Using the same key for every purpose would be a disaster for privacy, as it would cryptographically link all of your onchain activity together. The true power of this seed lies not in what it is, but in what it can become.

This is where the magic of derivation comes in. The process is governed by two key standards that work together to create a robust and interoperable system.

First is BIP-32, which defines the concept of a Hierarchical Deterministic (HD) wallet. Think of your master seed as the trunk of a cryptographic tree. BIP-32 provides the mathematical rules for how to deterministically generate a near infinite number of branches (child keys) from that trunk, and then smaller branches from those branches, and so on.

But with a potentially infinite tree, how does a wallet find any specific leaf? It is not enough to have a method for creating branches we need a shared map. This is the problem that BIP-44 elegantly solves. It doesn't introduce new cryptography rather, it proposes a well defined convention or a standardized "addressing scheme" for the BIP-32 tree.

A BIP-44 derivation path is defined as a five-level hierarchy:

m / purpose' / coin_type' / account' / change / address_index

purpose': A constant set to44'that identifies the BIP-44 standard.coin_type': Specifies the cryptocurrency, enabling multichain support from a single seed.account': Creates cryptographically isolated accounts for organizing funds.change: Separates external addresses (0) for receiving from internal addresses (1) for transaction change.address_index: The sequential index of the specific address being derived.

This power to create an infinite number of keys from one seed is the foundation of modern wallets. And it brings us to a crucial question if we can use this system to derive keys for our Ethereum accounts, why not use it to derive keys for applications that need secrets, like PrivacyPools or private messaging apps? This seems like an elegant solution to "seed fatigue".

However this is a dangerous path, a naive attempt to implement such a feature could open the door to catastrophic failure. To understand the risks, we map of the dangers in a series of attack vectors.

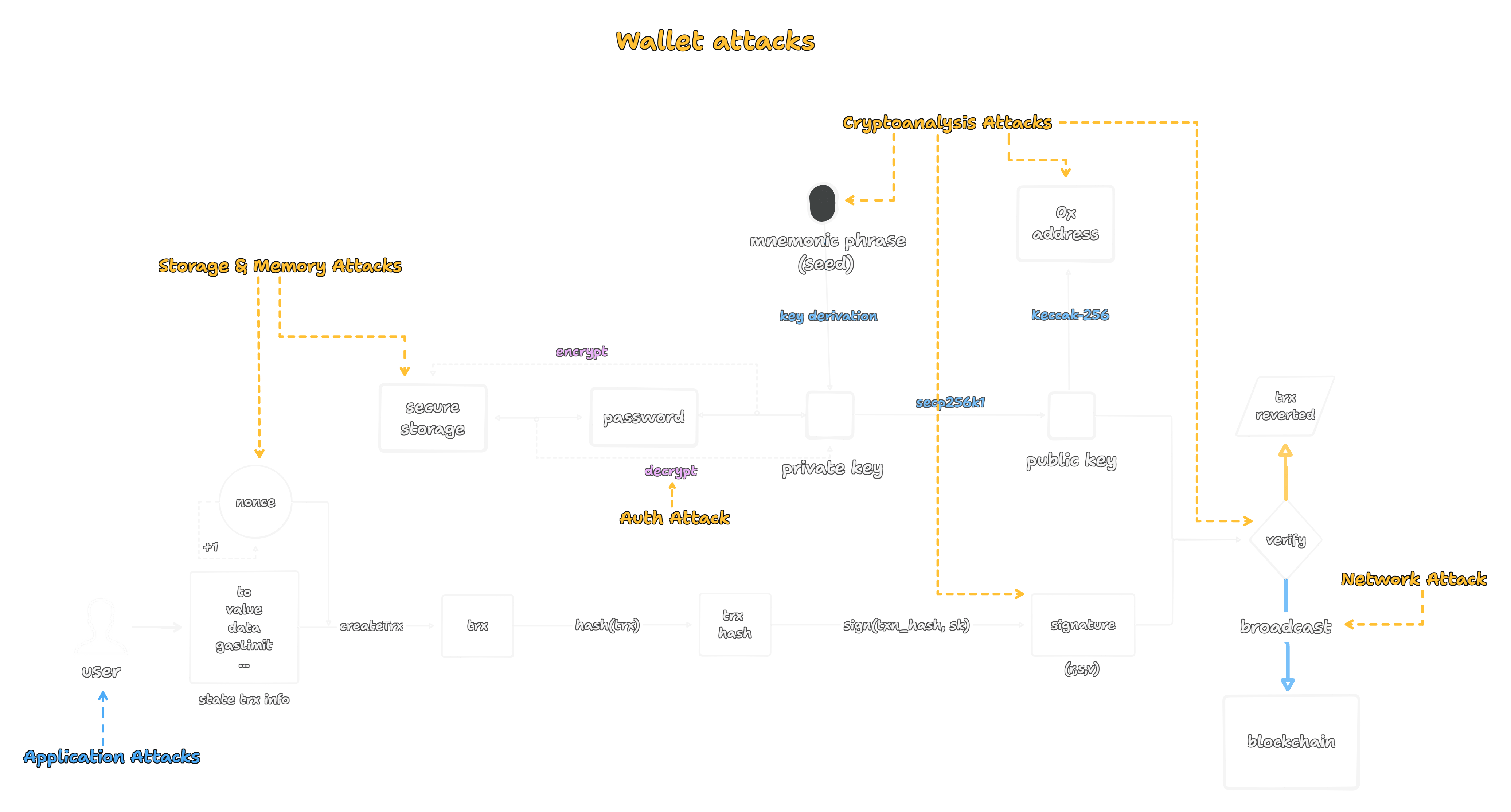

Application attacks

Application attacks are the most common threat. Such an attack could succeed not by breaking the protocol itself, but by exploiting a flawed implementation of it.

If a developer implements the protocol but makes a critical mistake like using the user's public wallet address for the derivation process instead of the special, undiscoverable Privileged-Access Address required by the signature derivation process that we will explain later. A phishing site, which already knows the target's public address, could then perfectly construct the exact same EIP-712 challenge that the legitimate application would create. The user would be prompted with what appears to be a valid request and, with one click, produce a signature. The attacker, having stolen this signature and knowing the public address used, could then run the final derivation step themselves and steal the user's appSecret.

The key insight here is that the protocol's security hinges on using a piece of information that is undiscoverable by the dApp. By tying the challenge to a hidden address that only the wallet can derive, the correct protocol creates an unforgeable link. An attacker simply cannot guess this address, making it impossible for them to construct the valid challenge needed to execute the attack.

Authentication attacks

Authentication attacks target the user's primary credentials. The goal is to crack or bypass the user’s authentication to gain unauthorized access to the wallet's core secret, the mnemonic phrase.

This is a threat that exists outside of any specific derivation logic. However, its implications are total. If an attacker compromises the master seed through a brute force attack or by stealing the user's mnemonic, then any deterministic derivation scheme is broken.

Storage & Memory attacks

This category includes attacks that extract secrets directly from a device’s memory or storage. This can be done via software, like malware that scans RAM for key-like data, or through sophisticated physical attacks like "cold boot" attacks or an "evil maid" modifying a device while the owner is away.

When a secret is derived, a critical question arises where does it live? In a naive implementation, the derived appSecret might exist in the memory of the host wallet software (e.g., the browser extension) or even passed to the dApp's JavaScript context. This memory is a relatively "soft" target. It is far more exposed and vulnerable to scraping by other malicious software on the host machine than the secure core of a hardware wallet.

A robust protocol must therefore consider the entire lifecycle of the secret. It is not enough to derive it securely; the protocol must also be designed to minimize both the exposure time and the footprint of the secret in vulnerable, general purpose memory spaces.

Cryptanalysis attacks

Cryptanalysis attacks are subtle. They don't break the underlying mathematical theory of the cryptography, but rather the implementation of it.

For a secret derivation protocol, this is a serious concern. If the derivation process itself involves cryptographic operations that are performed on a general purpose CPU, they could be vulnerable.

The key insight here is that the security of cryptographic operations is heavily dependent on the environment in which they are executed. A secure derivation mechanism should rely on cryptographic primitives running in a hardened, constant time environment designed to resist this kind of analysis.

Network attacks

This class of attack targets the communication channels between the user, their wallet, and the network. An adversary might try to intercept or alter data in transit.

In the context of secret derivation, this presents two primary dangers. First, an attacker could attempt to intercept the final expected output during its transit from the wallet to the legitimate application. Second, and perhaps more subtly, they could try to intercept and modify the request for a secret, perhaps swapping the intended application name for their own without the user's knowledge.

Therefore, any protocol for secret derivation must guarantee both the integrity of the request and the confidentiality of the derived secret as it moves between different components of the system, even under the assumption that the channel could be compromised.

Conclusion The Design Gauntlet

As we can see, what starts as a simple and appealing feature request to "derive application keys from my main seed" is in fact a journey through a minefield of security challenges. A naive solution fails on almost every front, creating a system that is arguably worse than having no solution at all.

Having now mapped the dangers and understood the various failure modes, we are better equipped to evaluate potential solutions. In our next discussion, we will explore our proposals that tackles these challenges and build a protocol that is both functional and secure.